By Frank Mitloehner

Millions of people grapple with the effect their lifestyle choices have on climate change, often leading them to draw comparisons between the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of their activities. But the discussion around emissions is full of nuances, and while we often search for easy analogies to paint a full picture of human-related climate impacts, they can create more confusion than clarity.

Case in point: I’ve recently come across several articles (here and here) comparing beef emissions with aviation emissions. They’re disappointing on many fronts. For starters, whenever we say a hamburger dumps more greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere than a trip on an airplane, we’re reinforcing a misunderstanding of the true GHG emissions of aviation. What’s more, we do it in a way that’s colorful, memorable and easy to latch on to.

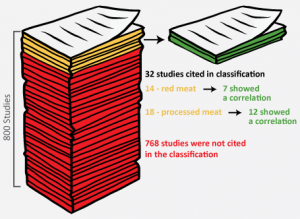

I can appreciate how having a sound bite is tempting and even useful like the recent Bloomberg assertion “… that the humble hamburger is a bigger contributor to the warming of the planet than the jumbo jet,” for example. The problem is, it’s not as simple as all that. Animal agriculture’s impact is overstated when speaking to an American audience, and aviation’s effect is understated when speaking to any audience.

U.S. livestock farmers have – and continue to – reduce GHGs

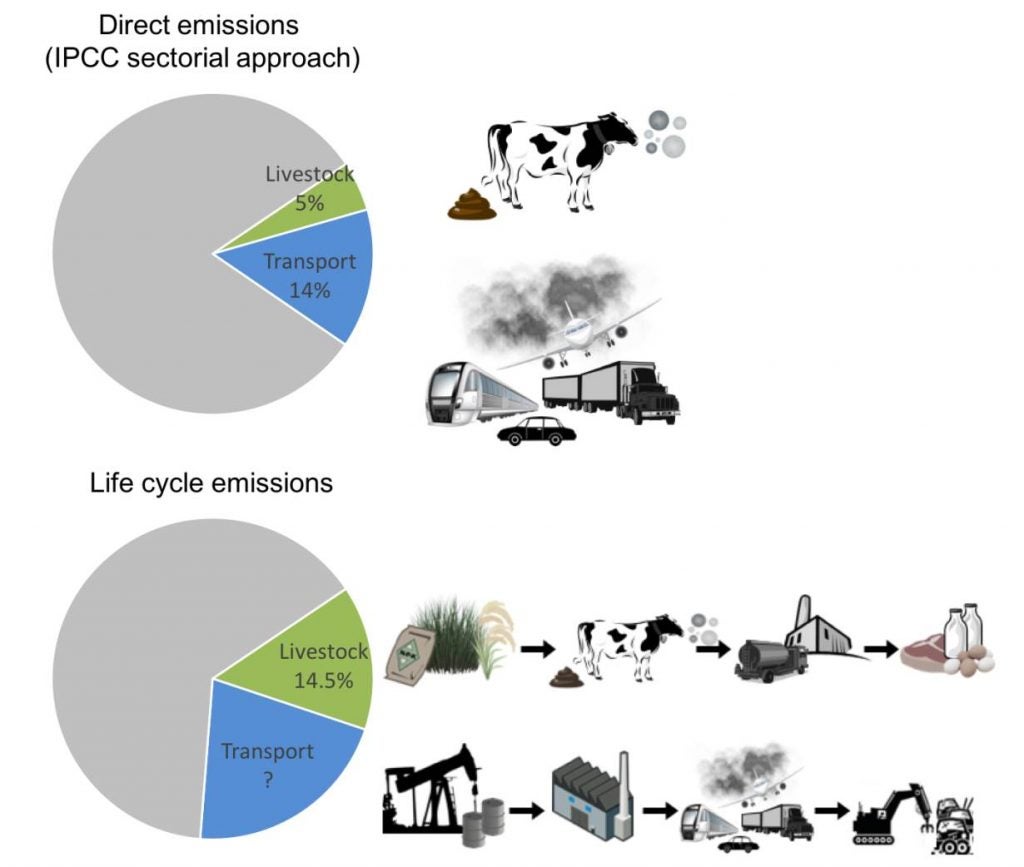

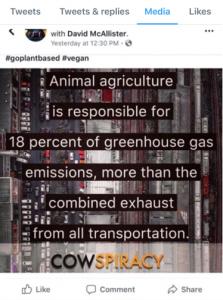

Globally, animal agriculture accounts for 14.5 percent of GHG emissions, the number that tends to be used to support the claim that eating meat is a bigger planetary enemy than the combustion of the fossil fuels used in aviation. But in the United States, isn’t it more helpful to look at U.S. animal agriculture statistics, especially when they’re vastly different from the global picture?

Here in the U.S., animal agriculture makes up a far smaller percentage of total GHG emissions than worldwide: 3.9 percent, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Granted, the lower U.S. percentage is due in some part to the fact that the United States is highly industrialized and wealthy, and we are major users of energy, fossil fuels and transportation. So as those percentages swell, animal agriculture takes up a smaller piece of the pie.

Even so, our farmers are the most efficient in the world. Case in point: In Mexico, it takes up to five cows to produce the same amount of milk as one U.S. cow, and in India, it takes up to 20. These statistics point to the United States having the lowest GHG emissions per unit of milk of any country in the world. It’s a similar story for other ruminant and non-ruminant animals that produce meat in the United States. In fact, emissions from all U.S. livestock species are much lower than those in Brazil, China, India and countries in the European Union, among others.

Americans fly more – much more – than people in any other country

Consistent with using a global number for animal agriculture is the tendency to do the same thing with the GHG emissions of air travel, and that likewise distorts the picture for the United States. Whereas the global animal agriculture figure is inflated for a U.S. audience, the global aviation figure downplays the role air travel plays in the United States’ GHG emissions.

That’s because Americans fly much more than people in other countries, including China, the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan, other top consumers of air travel. According to Bureau of Transportation Statistics, there were 1 billion passengers on U.S. airlines and foreign airlines serving the U.S. in 2019, a record and yet another year-over-year increase since the global recession of 2008-2009.

Aviation is two to three times more damaging to the environment than is often reported

In our hamburger-airplane example, aviation is assigned a GHG emissions number of 2 percent, giving most readers reason to have a clear conscience when boarding a plane. But that number doesn’t capture a plane’s full emissions footprint.

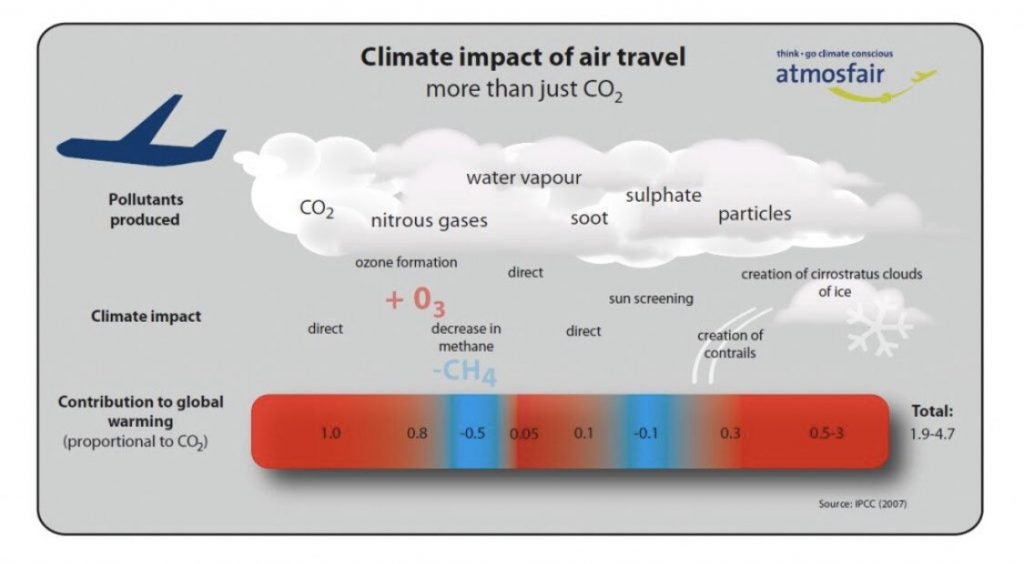

A 2 percent “GHG emissions” figure for aviation accounts only for the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) air travels puts in the atmosphere. It ignores, the other GHGs that come from planes (for example, nitrous gases, water vapor, soot, particles and sulphates).

Emissions from flying

In addition, the 2 percent number is a tailpipe assessment, meaning what is being measured are the direct CO2 emissions from the jet fuel that is combusted in the planes’ turbines. The figure fails to consider things such as the manufacture of materials for parts used in the aircraft, the transportation of materials and parts to factories where planes are made, wear and tear on roads and runways, and many more.

Life-cycle assessments and tailpipe emissions are GHGs’ apples and oranges

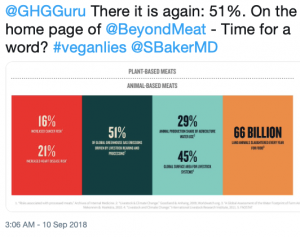

When we look at our metaphorical burger, we’re taking into account pretty much every GHG that is emitted by the activities and processes required to get the proverbial burger on a dinner table. Called a life-cycle assessment (LCA), it provides a more accurate and total picture of GHG emissions than does a direct (tailpipe) assessment.

In the same example, air travel gets a huge break by being subjected only to a measurement of its (direct (i.e. tailpipe) emissions. To make a fair comparison, the same system of quantification must be used for both the burger and the airplane ride, and ideally, a life-cycle assessment would provide the figures. The thing is, we don’t have life-cycle assessment numbers for planes, or other parts of the transportation sector.

Direct emissions vs. life-cycle emissions

Methane is a short-lived GHG; carbon dioxide might be forever

When we talk about the GHG emissions of livestock or the carbon footprint of meat, methane is often at the heart of the matter. Ruminant animals such as cows emit methane. As far as global warming potential, methane is a powerful GHG, with about 28 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide over a period of 100 years.

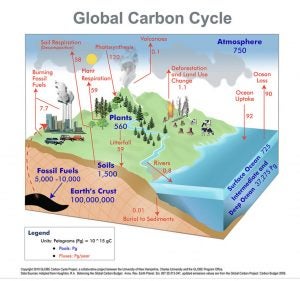

But methane doesn’t hang around for a century; it’s a short-lived GHG. In about a decade’s time, it’s converted to water vapor and carbon dioxide, which is part of the cycle whereby plants take CO2 out of the atmosphere and convert it into feed via photosynthesis. Animals eat the non-human edible vegetation and upcycle it to meat and dairy products that provide efficient sources of protein and other essential nutrients to humans. It’s a cyclical process, also referred to as the biogenic carbon cycle, that’s been around as long as life itself.

Given the advances American farmers have made in animal agriculture, today we are producing as much food as we did 50 years ago from cattle herds that are far smaller. All told, the U.S. herd is contributing less methane to the environment as a result.

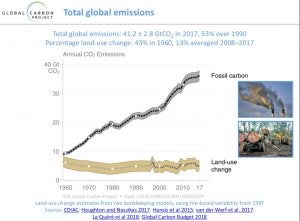

On the other hand, our voracious appetite for fossil fuels has resulted in an enormous glut of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. According to the EPA’s GHG inventory, CO2 accounted for 82 percent of GHGs in 2017, with industry, transportation and electricity contributing nearly 80 percent of the total. It’s so much more emissions than oceans, rainforests and plants can absorb, by conservative accounts, it will hang over the planet for a thousand years. Realistically, it could be forever.

The comparison between livestock and aviation has so many nuances, the chances for getting it wrong are high. And when we do get it wrong, we diminish the impact of major polluters. Can we afford to take such a gamble when the information might become the basis for public policy decisions we so desperately need?

As the saying goes, when pigs fly.

Frank Mitloehner is a Professor and Air Quality Specialist. Director, CLEAR Center. Department of Animal Science, University of California, Davis. You can follow him on Twitter at @GHGGuru.