By Frank Mitloehner and Darren Hudson

A story in The New Yorker came out this week about Dr. Pat Brown, the founder of Impossible Foods. If readers scan the headline and subhead, they’ll get the gist of what author Tad Friend is trying to say: “Can a plant based burger help solve climate change? Eating meat creates huge environmental costs. Impossible Foods thinks it has a solution.”

That’s unfortunate. It might even be dangerous. In the article, Mr. Friend writes that “Every four pounds of beef you eat contributes to as much global warming as flying from New York to London – the average American eats that much each month.”

If only.

For the record, since it’s not noted in the article, Mr. Friend is citing from the work of Tim Searchinger of Princeton University and the World Resources Institute. It suggests all one needs to do to hop on a transatlantic flight with a clear conscience is to forego a few weeks’ worth of burgers. Professor Searchinger asserts that reforesting all grazing lands and giving up three-quarters of beef and dairy would reduce total global greenhouse gas emissions by 20 percent.

It’s yet another example of misleading data that is misinforming readers and even worse, perhaps affecting public policy in a way that is detrimental to us and our planet.

Since the story came out this week, we shudder to think how many people have bought into the 4-pounds-of-beef argument that is stated upfront, incidentally. So, let’s dissect that number and try to set the record straight.

Four pounds of beef in the United States DOES NOT equate to the greenhouse gas emissions (per passenger) of a flight from New York to London.

Per passenger, a one-way flight from NYC to London causes 1,980 lbs (898 kg) of CO2 equivalent emissions (https://co2.myclimate.org/en/flight_calculators/new).

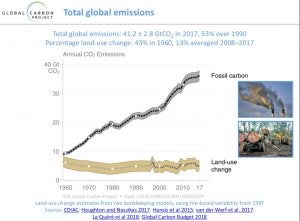

U.S. beef produces 22 kg of CO2 equivalent emissions per kg. Thus, 4 pounds of U.S. beef would result in approximately 40 kg of emissions, less than 1/20th of the emissions per passenger of the plane ride in question.

So how come that the New Yorker estimate is so far off reality? A premise in Professor Searchinger’s work is that beef yields 188 kg of CO2 equivalent per kg. But that’s his global number, and we’re talking to an audience of American readers. If you live and work in the United States and are in the market for a car, would you look at emissions from the global car-fleet average or from those in the United States? Of course, it’s the latter.

The most comprehensive cradle-to-grave (i.e. life-cycle) assessment for U.S. beef was recently conducted by a USDA Agricultural Research Service team led by Dr. Alan Rotz at Penn State. The team found that U.S. beef is responsible for 3.7 percent of total America’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Using a global number to represent U.S. animal agriculture is a disservice to American farmers – the most efficient in the world – and members of the American public who are making lifestyle choices based on the research they come across, whether it’s correct or not. It is also a disservice to Americans who expect that meaningful changes are being implemented to reduce climate pollutants. It is unquestioned by most experts, as well as by the Environmental Protection Agency, that fossil-fuel-intensive sectors, such as transportation, power and industry, emit approximately 80 percent of total U.S. GHG emissions. The plastic-straw-light-bulb-burger discussion that is frequently touted as a meaningful climate change solution seems to be a smokescreen to sidetrack from the major polluters.

Professor Searchinger, whose work is the foundation of the above mentioned assertion in The New Yorker article, has created a model of global marginal land use change and greenhouse gas emissions for beef. The core of his argument is that beef consumption anywhere will lead to global expansion of production and therefore puts pressure on, say, Brazilians to deforest in order to establish pasture. In a broad sense, supply must rise to meet demand. Taken a step further, he suggests if Americans stop reaching for beef as often as they do now, farmers and ranchers in the United States will turn to exporting more of their product, which will keep cattle producers in foreign countries from deforesting their homelands.

But Americans have already cut back on consumption, and companies have shifted to exports. In 1970, Americans consumed about 80 pounds of beef per person. Today? About 57 pounds. And in 1970, the U.S. exported less than 1 percent of its production but over 11 percent in 2018. Americans have long been doing their part according to this model. So, why is Brazil expanding its grazing area?

In short, they are different products serving different markets. Beef from Brazil is not the same as beef from the U.S., which specializes in producing well-marbled, grain-finished beef. Conversely, Brazilian beef exports tend to be grass-finished, leaner and in general lower-quality products. As a result, these two countries are producing beef for very different consumers – the U.S. is targeting higher-income countries for exports, such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, where demand growth is slower, whereas Brazilian beef is headed to lower-income consumers in countries such as China, Chile, Egypt and Iran, where demand growth is much faster. In short, any potential gains by U.S. consumption have been swamped by growing demand elsewhere.

Would increased U.S. beef exports eventually displace Brazilian beef exports in lower-income countries? Maybe, but it would take a considerable change in consumer choices and income in those countries. We have no evidence to indicate that would occur anytime soon, if at all. The predictions of the huge benefits of reducing U.S. beef consumption are, then, just based on unsupported assumptions.

Indeed, we live in a globalized world, but the beef market realities fly in the face of the globalized consumer model put forward by Professor Searchinger and the World Resources Institute. It’s just not that simple. Ultimately, a U.S. consumer eating less meat has not and will not displace consumption of Brazilian beef in Iran or China and therefore, decrease land expansion into the Amazon. That’s not how global beef markets work.

Solving the world’s climate change crisis is a weighty topic, and it is highly improbable (if not “impossible”) that an imitation beef burger is our savior. It is also a dangerous assertion, because it takes away focus from major polluters and our progress toward climate solutions.

Maybe – just maybe – American farmers and ranchers deserve some credit for efficiencies that for decades have decreased greenhouse gases while improving food production at unprecedented levels.

In short, for doing what the fossil fuel industry hasn’t figured out yet.

Frank Mitloehner is a Professor and Air Quality Specialist. Director, CLEAR Center. Department of Animal Science, University of California, Davis. You can follow him on Twitter at @GHGGuru.

Darren Hudson is a Professor & Combest Endowed Chair. Director, International Center for Agricultural Competitiveness. Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics. Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX. You can follow him on Twitter at @CompetitiveAg.