It seems we live in a time when people simply don’t know what to eat. Many of us want to do what’s right for our bodies and our planet, but we’re bombarded with conflicting messages or information that is just plain false.

On Nov. 7, 2018, news giant CNN, which touts itself as “the most trusted name in news,” reported a global meat tax could save 220,000 lives and cut health care bills by $41 billion each year. CNN’s report is based on a recent study from Oxford University.

“The numbers are based on evidence that links meat consumption to increased risk of heart disease, cancer, stroke and diabetes. Three years ago, the World Health Organization declared red meat such as beef, lamb and pork to be carcinogenic when eaten in processed forms, including sausages, bacon and beef jerky,” it said.

My life’s work centers on animal agriculture and air quality, and the goal of feeding a world population that will reach 10 billion in about three decade’s time. Information such as that put forth by CNN concerns me because meat’s connection to cancer has never been substantiated. Neither can one put the blame for heart disease, stroke and diabetes squarely on the shoulders of meat.

Peeling back the layers, today I want to take a half-step away from my day-to-day work to focus on the myth (perpetuated by many, including CNN yesterday) that eating meat, especially red meat and processed meat, can lead to cancer. My reason? We need – and will continue to need – animal protein to sustain human life. Without it, we simply can’t get enough essential nutrients for our global population. Buying into an unsubstantiated claim that red meat and processed meat lead to colorectal cancers (CRC) takes our eyes off the ball with nothing to be gained in return.

Partly to blame for the misconception is a 2015 study from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), part of the World Health Organization (WHO). The report tried to link meat with certain types of cancer, primarily CRC. This year, IARC released the full scientific basis of its finding, confirming just how weak the evidence linking meat and CRC is.

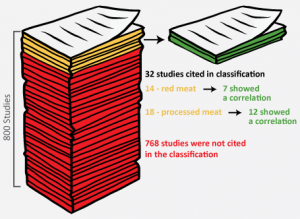

For instance, IARC claimed that 800 studies were used in its review, but in reality, nearly all were eliminated. Only 14 studies investigating red meat and 18 studies investigating processed meat were considered, and evidence showed deeply conflicting findings, not clear and convincing evidence. In the end, one has to wonder why it took IARC more than two years to present the evidence used to arrive at its 2015 conclusion, especially if that evidence was so bulletproof.

The message from IARC has been so misleading and has caused such confusion that its parent organization, WHO, came forward several years ago to deflate IARC’s claim and reassure the public that meat should be consumed in moderation as part of a healthy, balanced diet.

In addition, the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) states in relation to colon cancer, “There is no reliable evidence that a diet started in adulthood that is low in fat and meat and high in fiber, fruits, and vegetables reduces the risk of CRC by a clinically important degree.” In fact, the NCI takes it one step further, saying it’s “not clear” if diet affects the risk of colon cancer at all.

Professors Gordon Guyatt and Benjamin Djulbegovic, two leaders in evidence-based medicine, recently pointed out the minimal relative risk of meat leading to CRC: 1.17. Compare that to smoking, which makes one’s chances of developing lung cancer nine to 25 times greater, or to the fact that when IARC tested 1,000 substances for cancer-causing properties, only one – a chemical found in yoga pants – was found not to cause cancer. Further muddying the waters is the fact that it’s not possible to test meat’s connection to cancer in a vacuum. Other factors can’t be isolated easily, if at all. To that point, Professors Guyatt and Djulbegovic are correct in pointing out that vegetarians tend to be more alert to good health in general. They are more likely to exercise and refrain from smoking, at the same time coming from a higher-than-normal socio-economic class, some or all of which could have a bearing on the development of cancer.

If only cancer could be linked to a single cause. Who wouldn’t wish for that? However, cancer is a very complex disease that simply can’t be traced to one factor, let alone one food source. Genetics, physical activity levels and lifestyle habits (e.g., tobacco and alcohol use) play a role.

Putting a so-called “sin tax” on meat would only make it more difficult for consumers to access a food product that is vitally important to human health and survival now and in the future. Adding insult to injury is the fact that its upside (or promise) is negligible at best. There is no credible, science-based evidence to prove it would reduce cancer.

-Frank Mitloehner (@GHGGuru)